Courrier des statistiques N9 - 2023

Courrier des statistiques N9 - 2023

Distributional National Accounts: a new way to distribute growth - An Innovative experiment for public debate

Distributive accounts are used to study the distribution of national income among households. Redistributive impact of monetary benefits and taxes can be analysed together with the one of public services. Based on existing work and recent innovations, INSEE has developed a new approach referred to as distributive national accounts (DNA). The DNA is based on a method that connects individual data from social statistics to macroeconomic aggregates of national accounts. They provide a description of the distribution of national income and an estimate of the reduction of inequalities achieved thanks to all public transfers received or paid by households. Results can be presented by grouping households by income groups, age cohort or socio-professional categories and sub-national zone. The inclusion in the redistribution field of transfers in kind, such as health and education, and collective expenses, such as police, justice and local communities, is a major contribution. It enables international comparability and plays a major role in this expanded redistribution. The history, the method, the main results already published and the perspectives of DNA are presented in this article.

- Box 1: History of distributional accounts

- Box 2: Concepts and definitions of distributional accounting

- From national accounting to extended redistribution

- Reconciling the national accounts with social statistics

- Box 3: Distributing transfers according to variables other than income: it is possible.

- An unprecedented approach among statisticians and academics

- Box 4: Complementary international initiatives

- The general framework for the distribution of income and transfers based on individual data

- Supplementing individual data in order to distribute all transfers

- Taking better account of public services: innovation for transfers in kind and collective expenditure

- Lessons from extended redistribution

- Perspectives

Who benefits from growth? How is national income distributed among households? What is the redistributive impact of all public services? The purpose of distributional accounts is to answer these three key questions at the centre of economic discussions. They are part of a long history in which INSEE plays an important role. The first step was to reconcile the microeconomic social statistics data with the results of national accounting in order to study differences in income and consumption based on the heterogeneity of the situations of households. The household account then needed to be broken down according to household category. INSEE has recently developed an innovative approach to extending and supplementing these accounts for each household category. It aims to distribute all of the national income from all institutional sectors combined between households alone. It is based on distributional national accounts (DNA), established within the context of an expert group report (INSEE Méthodes No 138, February 2021). These studies form part of a body of statistical and academic literature seeking to expand the scope of redistribution and to reconcile microeconomic data with the accounting approach (Box 1). The DNA therefore makes it possible to analyse the reduction in inequality brought about by all public transfers from the perspective of an extended redistribution (Box 2). This extended approach to the primary distribution of income and to redistribution is based on a method that is described in this article.

Box 1: History of distributional accounts

The distributional accounts method is founded on long-standing ideas and a rich body of literature.

The latter started with a breakdown of the household accounts into categories that INSEE typically produces [Accardo and Billot, 2020]. Numerous studies carried out within official statistics since the 1980s have sought to complement the microeconomic approach to monetary redistribution by breaking down the national accounts (historical overview provided by Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAccardo, 2020). Between 1980 and 1985, INSEE published an annual income account for several dozen types of household in order to paint a picture of the budget of a household based on its socio-demographic characteristics. More recently, Accardo et al., (2009) proposed that household accounts be broken down by category for the year 2003 by combining the national accounting approach with the microeconomic statistics on inequality (working document by Bellamy et al., 2009). Disposable income and consumption in the national accounts are broken down according to four socio-economic criteria: standard of living, household composition, age, and socio-professional category of the reference person. This makes it possible to infer the saving rate for each of these various characteristics. This was the approach taken by Le Laidier (2009), and more recently by Billot and Bourgeois (2019), with a view in particular to comparing the annual changes in the accounts for each household category.

In addition, INSEE has published studies that broaden the scope of redistribution by integrating transfers “in kind” and individualisable public services [Amar et al., 2008] but do not cover collective public services, taxes on production or corporate consumption and taxation.

Some recent academic studies, most notably those by the World Inequality Lab [Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBozio et al., 2020; Alvaredo et al., 2020], also integrate taxes on production and products, but are based on general assumptions for benefits “in kind” and collective expenditure, which neutralise their effect on redistribution. These studies are backed by a network of researchers who are working to implement a concept similar to DNA, known as DINA (Distributional International National Accounts) in different countries around the world. They emerged in the wake of an influential publication by Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletThomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman (2018).

Box 2: Concepts and definitions of distributional accounting

- Standard of living (or usual standard of living) is the household’s disposable income divided by the number of consumption units (CU). The standard of living is therefore the same for all individuals in the same household. Consumption units are calculated according to the modified OECD equivalence scale, which assigns 1 CU to the first adult in the household, 0.5 CU to other persons aged 14 or over and 0.3 CU to children under the age of 14. If we arrange the distribution of standards of living in order, the deciles are the values that split this distribution into ten equal parts. The individuals classified in this way belong to standard of living tenths: the poorest 10% fall into the first tenth.

- A deduction is a transfer paid by households to public administrative bodies and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH). A benefit is a transfer received by households. These may be received in cash or “in kind”.

- The extended redistribution includes all public transfers from the various institutional sectors of the national accounts, including collective public services. In order to measure the impact of all of the deductions, benefits and collective expenditure, it compares “pre-transfer income” with post-transfer income, referred to as “extended standards of living”. The usual monetary redistribution focuses on taking account of monetary transfers (and not contributory benefits such as pensions and social security contributions).

- The net national income is obtained by deducting the consumption of fixed capital (CFC), which corresponds to the usury cost of the capital, from the gross national income. Gross national income is the sum of primary income received by resident economic units, themselves broken down within institutional sectors. It is equal to gross domestic product (GDP) minus primary income paid to non-resident economic units and increased by primary income received from the rest of the world by resident units.

Having detailed the accounting framework, the challenges of reconciling individual social statistics with macroeconomic data and of adopting a comprehensive overview of redistribution are discussed. The functioning and conclusions of the expert group made it possible to establish a distributional accounting method, which we then go on to explain. We conclude by describing the main lessons learned and the prospects for future studies.

From national accounting to extended redistribution

National accounting adopts a set of conventions around the concepts of income and production of economic agents. It is organised around institutional sectors (companies, households, government departments in a simplified version) that will produce and exchange goods and services. This accounting framework therefore makes it possible to establish large macroeconomic aggregates such as the value added of the national economy, gross disposable household income, economic wealth, etc. (Vanoli, 2002). Cross-sector exchanges, which are included in the table of integrated economic accounts, are described in detail and in the form of jobs or resources. Accounting tools, established thanks to titanic efforts to gather data and reconcile the various sources, are used to define the national income of an economy by deducting the balance of imports and exports from GDP (Lequillier and Blades, 2014).

The first essential step in the distribution of all national income to resident households is to consider households as the final recipients of the income from other institutional sectors (Figure 1). Companies are owned by households, either directly in the form of business assets or indirectly in the form of financial assets and savings. Likewise, public administrative bodies are ultimately allocated to households.

Figure 1 - From accounting framework to extended redistribution

It is then possible, based on the detailed measurement of the various incomes of the

institutional sectors and the transfers that take place between them, to define the

reduction of inequalities brought about by public transfers. The primary objective

is to take account of the fact that everything provided by the authorities is financed,

either directly or indirectly, by the population, and ultimately benefits the population,

again either directly or indirectly. In addition, a key advantage of this method is

that the exhaustive nature of the income and transfers that it includes allows for

robust comparisons between countries or between different periods within the same

country (see below). In particular, the breakdown of its various components, such

as pension or health expenditure, ensures the comparability of different international

systems, the social or public nature of which may differ. For this purpose, all national

income is allocated and distributed to resident households in France.

Two essential income concepts are therefore introduced:

- Pre-transfer income determines who “receives” the primary income. The main difference between this and primary household income is that profits reinvested in companies, i.e. corporate savings, are allocated to households, as well as the primary income of the public administrative bodies, the bulk of which is made up of taxes on production and products;

- Post-transfer income measures who “benefits” from (or “contributes” to) the public transfers. In particular, it adds a valuation of the services provided by public administrative bodies to household income.

The extended redistribution is measured for each household by the difference between these two key concepts and differs from the usual “monetary” measure (Figure 2). Monetary redistribution examines the most direct monetary transfers, i.e. deductions such as income tax, the general social contribution (contribution sociale généralisée – CSG) and monetary social security benefits (family benefits or statutory minimum incomes, for example).

Figure 2 - From usual monetary redistribution to extended redistribution

By distributing all of the net national income to resident households in France, the

extended redistribution takes account of deductions that have an indirect impact on

households, such as value-added tax (VAT) or excise duties (on tobacco and alcohol,

for example).

Extended redistribution also includes social security transfers “in kind” from the national accounts and public services rendered by means of collective expenditure (expenditure by public administrative bodies in areas such as health and education, as well as public services such as the police, the judicial system or central or local government services). The latter group of transfers is harder to directly account for than the former, but its quantification appears no less essential in view of the reality it represents and its scale if we are to precisely analyse the redistributive nature of the socio-fiscal system.

The comprehensive scope of extended redistribution therefore offers the advantage of “deducting” as much as it “pays” and vice versa. In this regard, it is considered to be balanced and allows for comparisons to be made over time and between countries. Indeed, in the case of a reform aimed at increasing or reducing VAT in return for a reduction or increase in income tax or social security contributions, for example, failure to take VAT into account in the analysis would introduce bias into any temporal and international comparisons. However, at this stage, this extended scope allocates all income to households without providing any information with regard to the heterogeneity of income or transfers beyond institutional sectors. As the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi report (2009) highlights, “going beyond GDP” is a strong and long-standing social demand. This means looking beyond accounting aggregates, which, when divided by the population, provide averages, and establishing income distributions and transfers to different categories of households. The distributional accounting method is combined with the tools of the distributional national accounts to measure the distortion of income distribution before and after transfers.

Reconciling the national accounts with social statistics

Based on the general accounting representation aggregated in this manner within a single institutional sector, namely households, the purpose of distributive economic accounting is to distribute some or all of these aggregates among households. It therefore documents the heterogeneity of the economic situations of different categories of households and, to an even greater extent, their inequality, based on national accounting concepts.

In order to do so, it cross-references macroeconomic accounting information with individual social statistics data. In the case of distributional national accounts, it takes the form of a table of integrated distributional accounts, inspired by the table of integrated economic accounts, which describes the sequence involved in the transition from distributive pre-transfer income to distributive post-transfer income. Transfers are made up of all deductions in the form of taxes, contributions and levies, or even monetary benefits and public services, in kind if they are individualisable, such as health or education expenditure, or collective such as expenditure on the judicial system, the police or defence. The before and after transfers profile, which is distributed to each household category, defines the extended redistribution between each household group (Figure 3 and Box 3). It then becomes possible to compare inequalities before and after, and, based on the difference, the extended redistribution, i.e. the way in which transfers help to mitigate primary inequalities.

Figure 3 - Different representations of extended redistribution by household group

Box 3: Distributing transfers according to variables other than income: it is possible.

Within the national accounts, income and transfers are allocated at the level of each household within the INES model,* which contains a vast array of socio-economic information. This method allows inequalities and redistribution to be analysed from various angles thanks to the ability to create different groupings.

The most conventional and intuitive of these is standard of living. In this case, individuals are classified into 10 or 20 equal groups according to their level of disposable income per household consumption unit (defined in Box 2). Each transfer is then allocated to an individual according to tax incidence assumptions, without changing the initial classification established on the basis of standard of living. Generally speaking, the assumption is made that the individual paying a certain tax is the one on whom the amount of the tax is indirectly dependent. Employers’ contributions therefore relate to employees since they are based on the payroll.

It is also possible to classify individuals according to characteristics other than standard of living: the age or level of education of the reference person of the household, the family configuration of the household, or place of residence (according to the size of the urban unit, for example). It is also possible to cross-reference variables (such as age with standard of living): it then becomes necessary to limit the categories to ensure that there are sufficient numbers of individuals within the samples.

* This model is based on data from the Enquête Revenus Fiscaux et Sociaux (Tax and Social Incomes Survey — ERFS), which makes it possible to simulate a large number of socio-fiscal transfers in detail, in particular social security benefits at the bottom end of the distribution (as well as certain non-monetary transfers) and social security contributions. It also allows us to ensure consistency of the incomes and transfers used by means of a central source, which is one of the recommendations made in the expert report (Insee, 2021).

The first step is to reconcile the coverage and conceptual differences between the macroeconomic aggregates of the national accounts and the various sources of microeconomic data. For example, retirement pensions and unemployment benefits are considered as deferred income in social statistics and fall within the definition of primary income (Sicsic, 2021). In both the national accounts and the distributional accounts, they are considered as transfers. This convention may contribute to changes in primary inequalities, particularly for wealthy, retired households, by classifying individuals based on their primary income. This is not the case when disposable income is the variable used to classify individuals and when this remains unchanged as recommended by the INSEE expert report (2021).

Another important factor is that the national accounts incorporate rents imputed to homeowners, in other words, a valuation of the housing service they provide to themselves. A household that owns the dwelling that it lives in does not pay rent, unlike a household that rents the dwelling that it lives in and leases the one that it owns. The national accounts therefore aim to equalise the situation by adding fictitious income to owner-occupiers equal to the amount that they would have paid if they were renting their dwelling. This allows for international comparisons, particularly between countries with different proportions of homeowners and tenants among households. This measure is not integrated into primary income within social statistics and is therefore not included in the poverty rate.

There are also discrepancies in the definition of disposable income applied by the two approaches. The housing allowances paid to low-income households who rent their dwelling are considered to be monetary benefits by social statistics, but as a transfer in kind within the accounting framework. As such, they are not added to household disposable income in the accounts. Distributional accounting follows this latter convention. Lastly, it should be noted that for the largest amounts, the national accounts, and therefore the distributional accounts, include a valuation for corporate fraud and illicit work in primary income, whereas this is not the case for social statistics.

An unprecedented approach among statisticians and academics

Several research and institutional studies have established distributional accounting (Box 4). Given the various different approaches, which in some cases result in contradictory conclusions, INSEE has taken the initiative to propose a joint working framework to the various teams involved in these approaches, made up of academics and statisticians, as well as government experts.

Box 4: Complementary international initiatives

INSEE’s studies form part of an international landscape in which multiple institutional stakeholders are interested in the distribution of accounting aggregates. Several countries are moving ahead with the recurring production of certain accounting aggregates. The majority of the discussions are taking place within the framework of the OECD, Eurostat* or UNStats**.

Due to the strong social demand for studies in these areas and the contribution of statistics of this type, the international landscape is changing rapidly at the institutional level. As part of the ongoing global revision of the System of National Accounts (SNA 2025), a chapter will focus on the distribution of accounts.

At the same time, various working groups and multilateral institutions are addressing the distribution of accounting aggregates. Most recently, Eurostat launched a dedicated task force for the purpose of accelerating the production of distributional accounts and making it a widespread practice.

The OECD has also carried out studies to this end. The Expert Group on Micro Statistics on Income, Consumption and Wealth (EG ICW) primarily focuses on the microeconomic coherence of data, but also works in conjunction with the Expert Group on Disparities in National Accounts (EG DNA), another OECD initiative that focuses on the microeconomic and macroeconomic coherence of distributional statistics. Several statistical institutes produce experimental statistics on this subject (Statistics Netherlands, 2014; Eurostat, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2018; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019). At this stage, the majority of these statistics are based on surveys and only cover a part of national income. The United States, Italy and Mexico are conducting similar studies into the role of transfers in kind or temporal series of distributional accounts.

Lastly, as part of the European PAS2 (Pan African Statistics) programme, resources have been allocated to INSEE by Eurostat for the purpose of supporting certain African countries in the preparation and development of distributional economic accounts by 2024.

* Eurostat is the community statistical institute, associated with the European Commission..

** UNStats is the United Nations Statistics Division.

The expert group focused on identifying the sources of the discrepancies between the existing studies, which were revealed to be down to the data sources used (survey or administrative database), differences in the method used to measure income (households or individuals, equivalence scales) and broader or tighter concepts of income, both before and after transfers. It is the latter, in particular, that results in notable differences. The usual approach is “monetary” redistribution, which takes account of direct taxes, social security contributions and cash benefits; the studies by the WIL also add taxes on production and products, including VAT; the OECD excludes the latter, but adds social security benefits in kind and individualisable public services, which INSEE also includes in its analyses, albeit on a less regular basis. None of these approaches takes account of fully collective public expenditure.

These studies gave rise to the publication of a report by INSEE (INSEE Méthodes No 138, February 2021), which collates the recommendations aimed at developing a unified framework for the establishment of distributional national accounts, together with a prototype for 2016. This report recommends in particular that as comprehensive an overview as possible be adopted of redistribution that reconciles all the different approaches, including all methods of financing and all types of public benefits or services. In this way, everything provided by the authorities is financed, either directly or indirectly, by the population, and ultimately benefits the population, again either directly or indirectly. The broader the concepts of income and redistribution, the more imputation assumptions are made. None of these approaches have any claim to replace the others; they must be regarded as different “halos” that provide complementary insights into inequalities and redistribution.

This report was followed up with publications by INSEE (see below) covering the overall framework of distributional accounting. The conclusions made by the expert group led to transfers in kind being better taken into account than in the WIL’s academic publications. Other statistical institutes, such as that of the Netherlands, have since adopted the method involving the distribution of expenditure in kind and the overall framework of distributional accounting (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBruil et al., 2022).

The general framework for the distribution of income and transfers based on individual data

During the estimation of DNA by INSEE, the distribution of income and transfers is largely achieved using the INES microsimulation model and the Enquête Revenus Fiscaux et Sociaux (Tax and Social Incomes Survey – ERFS) database (Figure 4). The latter is established on the basis of tax and social administrative data and the enquête emploi (Labour Force survey). The INES model is the primary distribution tool due to the large number of incomes and transfers that it includes. It makes it possible to distribute all deductions and monetary benefits (social security contributions, direct and indirect taxes, statutory minimum incomes, in-work benefits, etc.) among households, together with certain benefits in kind, such as the energy voucher.

Figure 4 - Data and sources used

It is primarily populated by the ERFS, but data is also taken from other databases

in order to simulate the maximum number of transfers. The documentation for the INES

model (Fredon and Sicsic, 2020), which collates in particular the discrepancies in the aggregated external data

(number of households concerned and total simulated transfers) allows for transparency

with regard to the findings of the distributional accounts.

In addition, a unified source allows for improved estimates when high numbers of incomes and transfers are distributed. This is because a single database would, for example, remove the need for assumptions based on statistical matching, which are technically flawed; too great a diversity of sources would result in “noisy” estimates. This would be all the more damaging given that it is a case of cross-referencing variables and distributing them to household categories. The DNA therefore favours the INES model database, which, by design, includes a wealth of information regarding the households of which it is composed.

Each transfer is allocated to an individual in accordance with tax incidence assumptions based on information provided by the INES model. For example, social security contributions are allocated to and therefore paid by employees and dividends are allocated to and paid by shareholders. The income and transfers included in the ERFS and INES are then calibrated to the data from the national accounts using the correspondence table established by the Expert Group on Inequality and Redistribution. At this stage, it is necessary to fill any gaps in the coverage of individual data using the full coverage provided by the national accounts. By design, and in particular due to the sampling plan for INSEE’s household surveys, the ERFS covers 93.5% of the French population. In order to fill this gap, the income and transfers of the population falling outside the scope of the survey are distributed by reproducing the distribution indicated in the ERFS. This assumption is satisfactory, in so far as the coverage of income and the main deductions provided by the ERFS is generally around 90%.

By way of illustration, the INES model makes it possible to simulate, and therefore distribute, around 430 billion euro of social security contributions, against a total of 480 billion euro in the national accounts, so around 90%. This partial coverage is primarily linked to the difference in coverage and, to a lesser extent, an imperfect simulation of contributions. The 10% not simulated by the INES model are, according to the assumption applied, distributed in the same manner as the 90% simulated by the model.

All this results in the ability to create a large database of households, including their primary incomes and transfers with values equal to those established in the national accounts, and to distribute those incomes and transfers according to different variables (Box 3).

Supplementing individual data in order to distribute all transfers

However, some transfers are not present within the ERFS data or the INES model due to a lack of information. This is the case in particular for corporate tax (CT) and retained company profits. Their distribution therefore requires imputation or simulation assumptions. An initial assumption is based on the concept of income from business ownership and assumes distribution in the same way as dividends paid (variable present within the ERFS data), following the incidence rule mentioned previously. Indeed, since companies are owned by shareholders, the assumption serves to allocate to the latter the profits made and the CT paid by companies. In an ideal world, the tax incomes of individuals would be linked directly to the characteristics and results of the companies that they own, but this would require far more in-depth work than the initial estimates of the distributional national accounts. Official statistics work is under way with a view to taking account of shareholders who own companies with a significant stock market valuation but do not pay dividends. Other redistribution assumptions are possible, based on income from assets, broadly speaking, or assets held, for example; however, they have little impact on the overall redistributive profile [Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPiketty, Saez and Zucman, 2018]. Some specific transfers, such as transfer taxes or low-yield taxes, or even cultural and associative activities, which represent smaller amounts and are not measured by means of individual data, are distributed according to the transfer profile of the same accounting category, but one for which the profile is known thanks to microeconomic data.

Lastly, a key point highlighted by these studies, and one that had not yet been closely addressed by some academic studies, is the accurate consideration of public services. We therefore pay particular attention to healthcare, education and collective expenditure due to: (i) the magnitude of the amounts involved, (ii) the specific methodological and conceptual issues that they raise, (iii) the specific nature of the data used, which differs from those provided by the ERFS/INES, (iv) their innovative nature (none of the previous literature has ever attempted to distribute these together with other transfers). Indeed, many studies have estimated the redistributive effect of healthcare or education separately, but there has been no contribution that estimates the redistributive impact of transfers in kind and collective expenditure taken as a whole.

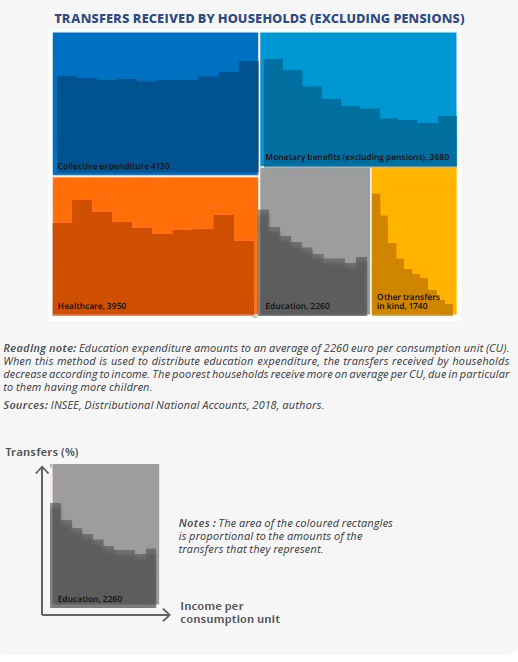

Taking better account of public services: innovation for transfers in kind and collective expenditure

Due to their importance in the net national income (NNI) in France (30%), it is crucial that expenditure in kind and collective consumption are taken into account in the redistribution. Whether they relate to healthcare expenditure covered by social security or free primary and secondary education, transfers in kind are a part of the daily lives of households in France. In 2018, for example, collective consumption expenditure represented 10% of the NNI and an annual average of 4130 euro per consumption unit (CU). As regards benefits in kind, the primary areas of expenditure, namely healthcare and education, represent 9% and 5% of the NNI respectively, i.e. 3950 and 2260 euro on average per CU (Figure 5). Conversely, in the United States, private schools are common and social security does not exist in the same way as in France: healthcare and education expenditure is largely financed directly by households. Failure to take account of public services such as education and healthcare would result in an underestimation of redistribution in European countries, where these services are particularly widespread.

Figure 5 - Amounts (in euro per consumption unit) and profiles of transfers received by households

Given the amounts associated with these transfers, the challenge is therefore to meticulously

assign a value to the distribution of public services. In the absence of precise information

regarding individuals, assumptions must be made regarding the distribution of such

expenditure: for example, distribution similar to that observed for primary income,

in a uniform manner (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPiketty, Saez, Zucman, 2018; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBozio et al., 2020), or even by using aggregated data (OCDE, 2013). In the initial publications of INSEE’s distributional accounts in France (Accardo et al., 2021, André, Germain and Sicsic, 2023), such expenditure was simulated in detail using complementary microeconomic data.

Healthcare expenditure is distributed based on reimbursements from compulsory health insurance, as well as from supplementary health insurance using the DREES INES-OMAR (Outil de Microsimulation pour l’Analyse des Restes à charge – Microsimulation Tool for Analysing Out-of-Pocket Expenditures) model [Lardellier et al., 2012]. This model is based on the Enquête Santé et Protection Sociale, a survey on health, access to healthcare and insurance (ESPS-EHIS), matched with administrative data providing detailed data concerning the consumption of healthcare (système national de données de santé – SNDS (National Health Data System)), as well as on the DREES survey of the most popular contracts taken out with supplementary insurers and the Enquête Statistique sur les ressources et les conditions de vie (Statistics on resources and living conditions survey – SRCV), in particular its module concerning supplementary healthcare coverage and perceived state of health. The model is compared with the INES model, which makes it possible to break down the amounts reimbursed by health insurance according to the standard of living of individuals or other characteristics (socio-professional category, level of education, age, etc.) and to include the financing provided by the sickness element of social security. When this method is used to distribute healthcare expenditure, the transfers received by households based on income are relatively consistent (Figure 5).

Education expenditure is distributed in several steps. The first step is to multiply the average cost per pupil from primary school through to high school, taken from the education account, by the number of children concerned, based on the age and number of children entered in the ERFS. Children and pupils over the age of 14 who are present within the household provide a precise indication of the type of education they are pursuing in the ERFS, which makes it possible to distinguish between general and vocational high school, higher education vocational courses (STS), preparatory classes for grandes écoles (CPGE) and university. The average costs of each type of training are used to determine the education expenditure received by each individual with a relatively high level of precision. Students who are not cohabiting are linked to their parents’ households based on the Enquête sur les Ressources des Jeunes (Survey on the Resources of Young People – ENRJ) conducted by INSEE and DREES in 2014 in order to take account of intra-family transfers. Failure to take account of these transfers could actually generate surplus expenditure at the bottom end of the distribution due to students from wealthy families being incorrectly classified at the bottom end of the distribution (Figure 5).

Collective consumption expenditure is split in two. The collective consumption expenditure referred to as “locatable” (police and justice, as opposed to defence or foreign affairs, for example) is distributed on the basis of the payroll of the officials concerned (with the exception of hospitals and teaching, which are accounted for as healthcare and education expenditure). Based on Annual Social Data Declarations (déclarations annuelles de données sociales – DADS) and Nominative Social Declarations (déclarations sociales nominatives – DSN), public services are located for each living zone. The ratio between the payroll of these officials and the number of individuals is allocated to each ERFS household in order to measure the collective expenditure within their living zone. This method results in a relatively uniform profile ordered by standard of living; however, the expenditure is slightly higher for the poorest and wealthiest households (who are more likely to live in large cities and have greater access to public services). Conversely, collective consumption expenditure that is allocated nationally, such as defence, foreign affairs and civil servants working in general government is distributed on a flat-rate basis, since such expenditure benefits the entire population. According to Accardo et al., (2022), distributing such “national” collective expenditure in proportion to income leads to a relative decrease in income of between 500 and 800 euro per consumption unit (depending on the income taken into account for the redistribution of this expenditure) for the poorest 10% and an increase of 1000 to 1500 euro for the wealthiest 10%. Although it is not neutral, this effect remains within the scale of the broader redistributive profile, since expenditure allocated nationally only represents around 20% of collective expenditure. The impact would be much greater if the assumption of proportionality were adopted for all collective expenditure.

Lessons from extended redistribution

Distributional national accounts provide a new perspective on inequalities and redistribution in France. They offer a tool to supplement existing schemes and allow for a better understanding of who receives what and who pays what in France. However, it is important to bear in mind that distributional national accounts are based on abstract concepts that do not reflect the perceived reality of individuals. For example, pre-transfer income, i.e. “primary” income, is higher than the income that individuals actually see in their bank accounts. In addition to contributions from employers, it also includes retained company profits, rents imputed to homeowners and certain indirect taxes on production and consumption depending on the assumptions made. Likewise, social security transfers in kind and public services rendered by means of collective expenditure are free of charge or almost free of charge and therefore differ from the monetary reality represented by monetary benefits such as family allowances, for example.

This monetary valuation of public services defines an extended income after redistribution. This does not reflect a tangible monetary reality for households. Such quantifications are essential if we are to thoroughly analyse the redistributive nature of the socio-fiscal system; however, this study reflects an accounting valuation rather than the amount that households can actually receive.

The first distributional national accounts exercise involving the general public based on household level covered the year 2018 (Accardo et al., 2021). The redistribution-related reduction in inequality is twice as great using the extended approach when compared with the usual monetary approach. The redistributive nature of the French socio-fiscal system comes primarily from transfers in kind, such as education, healthcare and housing, which are responsible for 50% of the reduction in inequalities. Collective public services also contribute significantly to reducing inequalities thanks to their relatively uniform distribution among the population.

In the exercise for the year 2019 (André et al., 2023), new findings are presented according to different variables: age, level of education, family configuration, gender and even socio-professional category. Around 60% of individuals are net beneficiaries of redistribution in that they receive more than they contribute. These net beneficiaries of the extended redistribution are largely pensioners and the poorest households, but families with children, households with a lower level of education and unskilled workers also benefit, albeit to a lesser extent. Conversely, wealthier people, those without children, people living in urban areas (and in particular in the Paris conurbation), people in good health and those aged between 40 and 60 years receive less than they pay in contributions on average. Distributional accounts are also used to study redistribution according to the category of municipality and their type of urban area (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAndré, 2022).

Perspectives

Distributional accounts as established by INSEE are expected to become more widespread, as they meet a strong social demand, expressed in particular in the studies conducted by the CNIS, as well as in the research studies contributing to the broadening of the concept of income inequality. The intention is therefore for distributive economic accounts to incorporate international standards for the national accounts: work is under way in this regard under the aegis of the United Nations (UN) and is looking at the breakdown of the household sector into categories (UN-STATS).

INSEE is working on developing temporal series of distributional accounts in order to distribute the additional funds brought by growth (of the national income, which is very close to GDP growth) between categories of households, while also ensuring comparability across time and space. This may help to identify the main beneficiaries of growth over different periods (annual or between two dates, a decade for example). The intention is to produce the distributional accounts on an annual basis, both in the form preferred by the international framework, namely the distribution of aggregates within the household sector (Accardo and Billot, 2020), as well as in the extended form of distributional national accounts, as described in this document. With a view to integrating these methods into the national accounting tools, INSEE has decided to deepen its technical expertise. A retrospective analysis will make it possible to examine the appropriate time frame for providing such accounts, downstream of social statistics. In addition, particular attention will be paid to the readability and consistency of the messages issued by the Institute with regard to inequalities and how they are evolving. Putting these distributional accounts into production will ensure their continuity and ensure regular publication. Ambitious longer-term prospects would aim to establish quarterly distributions of inequalities (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBlanchet, Saez and Zucman, 2022). However, there are a number of methodological barriers to this, starting with the challenge of using infra-annual administrative data on income and transfers.

One possibility that could be looked into in order to make these projects a success and to improve the quality of the distributional accounts would be to supplement the INES model with data from FIDELI, FILOSOFI and EDP-santéwith a view to improving the data at the extreme ends of the distribution as well as with regard to healthcare expenditure. A project is under way between INSEE and the Directorate-General for Public Finance (Direction générale des finances publiques – DGFiP), which aims to reconcile household and corporate data in order to better measure the impact of taxes on production (in particular corporate tax) and to issue fewer imputation assumptions with regard to the distribution of retained earnings. Other national institutes are also working on expanding the usual coverage of the analysis of inequalities, in particular by incorporating transfers in kind. It is also worth looking into improving the information available with regard to education using localised expenditure data for children and students linked to their parents’ household and making use of the DSN to improve the distribution of local collective public expenditure. Lastly, as a follow-up to the studies already produced by INSEE with regard to the breakdown of national income, a next step could be to create a distributive account for household wealth by clarifying the coherence between national accounting concepts and data, tax data and the enquête Patrimoine (Household Wealth survey).

Paru le :29/10/2024

The “by category” accounts refer to a household sector distributive account (compte distribué du secteur des ménages – CDSM) and aim in particular to identify variations in savings rates between the different categories of households. They are therefore limited to the institutional household sector (S14) and the gross disposable income of households, which is compared with their consumption.

The various stakeholders in economic life are grouped into five resident institutional sectors based on their economic behaviour: non-financial corporations (NFCs), financial corporations (FC), public administrative bodies (PAB), households and non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH).

A correction is made with the rest of the world for corporate savings held by non-resident households and foreign company savings held by residents.

Some analyses of monetary redistribution may take account of contributory benefits (pensions and unemployment insurance) and social security contributions.

They come from the Ministerial Statistical Offices involved, the OECD and the academic teams of the World Income Lab (WIL) and the Public Policy Institute (Institut des Politiques Publiques – IPP) at the Paris School of Economics, the French Economic Observatory (Observatoire français des conjonctures économiques – OFCE) and the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Evaluation of Public Policy (Laboratoire interdisciplinaire d’évaluation des politiques publiques – LIEPP) at Sciences-Po.

The overseas departments, non-standard dwellings and households in which the reference person is a student or declares negative income tax are not covered.

This is performed at a finer level of contributions. The greatest discrepancy between the amounts simulated by the INES model and the national accounts relates to contributions to individual social protection schemes (which represent 2% of NNI) as these are not simulated by INES. However, the other contributions are simulated, which renders the assumption less robust. The distribution of these known contributions is replicated for the individual social protection schemes category.

It is a case in particular of reconciling administrative sources of household and company data as well as information regarding the ownership of companies.

This is the case for certain social action transfers outside of the personalised autonomy allowance (allocation personnalisée d’autonomie) and the childcare supplement (complément de mode de garde), which are simulated by INES and distributed as family benefits, or special taxes on insurance policies, which are distributed as taxes on insurance premiums (simulated by INES).

The Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques (Directorate of Research, Studies, Evaluation and Statistics – DREES) is the ministerial statistical office covering the areas of healthcare and social affairs.

The National Council for Statistical Information (Conseil national de l’information statistique – CNIS) facilitates interactions between the producers and users of official statistics.

FIDELI (Fichiers démographiques sur les logements et les individus – demographic files on dwellings and individuals) is a statistical repository of tax, social and income data (Lamarche et al., 2021). FILOSOFI (a localised social security and tax data file) is an income database. The EDP-santé (EDP-health Robert-Bobée et al., 2021) is an enrichment of the Permanent Demographic Sample using data from the National Health Data System (système national des données de santé – SNDS).

One disadvantage of using the ERFS and the INES model is the granular nature of the results due in particular to the random nature of the sample, which could, in theory, include more people at the extreme ends of the population as a result of the huge variations in income. Therefore, special attention must be paid to analyses by hundredths. In the expert report (Insee, 2020), statistics for the top 1% of distributional accounts were compared using INSEE’s ERFS-based method and the method used by the World Income Database (WID) teams, which is based on comprehensive data: the results were found to be very similar with identical coverage and methods.

Pour en savoir plus

ACCARDO Jérôme, BELLAMY Vanessa, CONSALES Georges, FESSEAU Maryse, LE LAIDIER Sylvie and RAYNAUD Émilie, 2009. Les inégalités entre ménages dans les comptes nationaux : une décomposition du compte des ménages. In : L’économie française, coll. « Insee Référence » [Online]. 25 June 2009. pp. 77-101. [accessed 21 March 2023].

ACCARDO Jérôme, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSupplementing GDP: Some Recent Contributions from Official Social Statistics. In : Economie et Statistique / Economics and Statistics, n° 517-518-519. 8 October 2020. [Online]. pp. 25-39. [accessed 21 March 2023].

ACCARDO Jérôme and BILLOT Sylvain, 2020. Plus d’épargne chez les plus aisés, plus de dépenses contraintes chez les plus modestes. Insee Première n° 1815, [Online]. September 2020. [accessed 21 March 2023].

ACCARDO Aliocha, ANDRÉ Mathias, BILLOT Sylvain, GERMAIN Jean-Marc and SICSIC Michaël, 2021. Réduction des inégalités : la redistribution est deux fois plus ample en intégrant les services publics. In : Revenus et patrimoine des ménages, coll. « Insee Références » [Online]. 27 May 2021, pp 77-96. [accessed 21 March 2023].

AMAR Élise, BEFFY Magali, MARICAL François and RAYNAUD Émilie, 2008. Les services publics de santé, éducation et logement contribuent deux fois plus que les transferts monétaires à la réduction des inégalités de niveau de vie, In « Vue d’ensemble — Redistribution », France, portrait social, coll. « Insee Références ». [Online]. 1st November 2008. [accessed 21 March 2023].

AUSTRALIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAustralian National Accounts: Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth, 2003-04 to 2017-18. [accessed 21 March 2023].

ANDRÉ Mathias, 2022. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLes prélèvements obligatoires au regard des enjeux redistributifs. In : rapport particulier n° 3 pour le Conseil des prélèvements obligatoires. [Online]. February 2022. [accessed 21 March 2023].

ANDRÉ Mathias, GERMAIN Jean-Marc and SICSIC Michaël, 2023. ‘Do I get my money back?’: A Broader Approach to Inequality and Redistribution in France With a Monetary Valuation of Public Services. In : Documents de travail. N° 2023-07 [Online]. 8 March 2023. Insee. [accessed 21 March 2023].

BELLAMY Vanessa, CONSALES Georges, FESSEAU Maryse, LE LAIDIER Sylvie and RAYNAUD Émilie, 2009. Une décomposition du compte des ménages de la comptabilité nationale par catégorie de ménage en 2003, In : Documents de travail. [Online]. N° G2009/11. [en ligne]. 1st November 2009. Insee. [accessed 21 March 2023].

BILLOT Sylvain and BOURGEOIS Alexandre, 2019. Quelle(s) mesure(s) du pouvoir d’achat ?, In : L’économie française – Comptes et dossiers, coll. « Insee Références ». [Online]. 28 June 2019 [accessed 21 March 2023].

BLANCHET Thomas, SAEZ Emmanuel and ZUCMAN Gabriel, 2022. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletReal-Time Inequality (July 2022). NBER Working Paper No. W30229 [Online]. 12 July 2022 [accessed 21 March 2023].

BOZIO Antoine, GARBINTI Bertrand, GOUPILLE‑LEBRET Jonathan, GUILLOT Malka and PIKETTY Thomas, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletPredistribution vs. Redistribution: Evidence from France and the U.S World Inequality Lab – Working Paper N° 2020/22. [online]. [accessed 21 March 2023].

BRUIL Arjan, VAN ESSEN Céline, LEENDERS Wouter, LEJOUR Arjan, MOHLMANN Jan and RABATÉ Simon, 2022. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletInequality and Redistribution in the Netherlands. CPB Discussion paper [online]. [accessed 21 March 2023].

EUROSTAT, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletIncome and consumption: social surveys and national accounts. In : site de Eurostat. [Online] [accessed 21 March 2023].

FREDON, Simon and SICSIC, Michaël, 2020. INES, the Model that Simulates the Impact of Tax and Benefit Policies. In : Courrier des statistiques. [Online]. 29 June 2020. Insee. N° N4, pp. 42-61. [accessed 21 March 2023].

INSEE « Expert Group Report on the Measurement of Inequality and Redistribution », sous la direction de J.‑M. Germain (rapporteurs : André, M. et Blanchet, T.), Insee méthodes n° 138. [Online]. February 2021. [accessed 21 March 2023].

LAMARCHE, Pierre and LOLLIVIER, Stéfan, 2021. Fidéli, l’intégration des sources fiscales dans les données sociales. In : Courrier des statistiques. [Online]. 8 July 2021. Insee. N° N6, pp. 28-46. [accessed 21 March 2023].

LARDELLIER Rémi, LEGAL Renaud, RAYNAUD Denis and VIDAL Guillaume, 2012. A Tool for the Study of Total Household Health Expenditures and Out-of-Pocket Expenditures: The OMAR model. In : Économie et statistique. [Online]. 30 November 2012. Insee. N° 450, pp. 47-77. [accessed 21 March 2023].

LE LAIDIER Sylvie, 2009. Les transferts en nature atténuent les inégalités de revenus. [Online]. November 2009. Insee Première n° 1264. [accessed 21 March 2023].

PIKETTY Thomas, SAEZ Emmanuel and Zucman Gabriel, 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDistributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States. In : Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133 (2), pp. 553-609, [Online]. 10 October 2017. [accessed 21 March 2023].

ROBERT-BOBÉE, Isabelle and GUALBERT, Natacha Gualbert, 2021. L’échantillon démographique permanent : en 50 ans, l’EDP a bien grandi ! In : Courrier des statistiques. [Online]. 8 July 2021. Insee. N° N6, pp. 47-63. [accessed 21 March 2023].

STATISTICS CANADA, 2021. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDistributions of Household Economic Accounts, estimates of asset, liability and net worth distributions, 2010 to 2021, technical methodology and quality report. [Online]. 3 August 2022. [accessed 21 March 2023].

STATISTICS NETHERLANDS, 2014. Measuring Inequalities in the Dutch Household Sector.

STIGLITZ Joseph, SEN Amartya and FITOUSSI Jean‑Paul, 2009. Rapport de la Commission sur la mesure des performances économiques et du progrès social. Éditions Odile Jacob, 13 November 2009. ISBN 978-2-7381-9380-3.

VANOLI André, 2002. Une histoire de la Comptabilité nationale. Paris, La Découverte, 2002, p 656.